It could just be my obsession with quality sitcoms, but the entire time I was playing Undertale I couldn’t help but be reminded of, among many other things, NBC’s Community, specifically the character of Abed Nadir. The thing about Abed’s character was that he simply didn’t really make much sense within the context of actually being a character on a TV show. Of course, he worked excellently, since one of the things Community excelled at was being a very strange show. Abed’s shtick was that, most of the time, he seemed to be aware of the fact that he was on a sitcom, and it was taken as far as it logically could be within the scope of not having too large of a bearing on the plot.

Abed would constantly reference the mayhem and mania that took place on the show and point them out to the viewer through the lens of acting as if he were on a TV show, which, of course, he was. He would point out continuity errors, obvious plot devices, and gimmicks that only work on TV shows, and did so in a very tongue-in-cheek way that simply made the viewer feel like they were in on the joke, and not being patronized. TV Tropes calls this method of pointing out something that could otherwise be perceived as a flaw, and in doing so turning it into a joke, as “lampshading.” And Abed was excellent at it.

One particular instance involved a “bottle episode”, wherein, in order to preserve budget, an episode of a show (usually a sitcom) would take place all on one set, and with only the principle cast. Every sitcom’s done it, and Cheers’s entire first season comes to mind in particular as being made entirely out of bottle episodes. At any rate, when the bottle episode on Community eventually came around (it’s sort of a rite of passage for sitcoms these days, as they rely heavily on the quality of the characters and writing and not much else), Abed blatantly pointed it out, and said “This is a bottle episode. I hate bottle episodes. They’re wall-to-wall facial expression and emotional nuance.” Anyway, you get the idea. This is a long-winded introduction, but it really hits on what I love about Undertale. Abed was a great character because he had perfect awareness of the medium he was being portrayed in, and the writing used it to make great jokes, and ones that only fans of sitcoms would truly appreciate. Undertale does the exact same thing, but for video games.

The great thing about Undertale is how brutally consistent it is. It’s also what makes it very frustrating, and also very funny. Much like my favorite TV show of all time (Arrested Development), Undertale really needs to be enjoyed all in a short span of time to really appreciate everything going on here. I played it over the course of three days, and loved its remarkable consistency and the perpetuation of a few key elements that the game’s creator decided at the forefront to include.

The game, after all, was largely made by one person — Toby Fox — and I laud his efforts here. It’s not much to look at, but that’s really the only downfall. Being a student of computer science, I naturally spend most of my time playing a game contemplating what went into it. Undertale’s interesting because it doesn’t really strike me as being that hard to make (which isn’t to say I could do it, by any stretch of the imagination). Some games are great because they’re a technological marvel, ie. The Witcher 3, but Undertale is great because the ideas here are so, so damn good.

The crux of the game is that it’s an RPG with lots of enemies to fight, and you don’t have to kill any of them. Which, okay, I guess other games have done that before. But not nearly in so great a way as Undertale does. Every single enemy you fight has a story to tell, and the path to avoiding conflict with it and progressing peacefully is hidden in a puzzle-like dialog tree wherein you need to figure out exactly what it is you need to tell this particular monster or do for it to get it to leave you alone. For instance, a dog-type enemy might want you to call it, pet it a few times, and then play with it a while before it falls asleep and lets you continue. A … horse mermaid … thing, with great abs, wants to engage you in a flexing contest, so you might have to flex a whole bunch of times before he “flexes himself out of the room”.

Of course, the fights aren’t easy, thanks to the ingenious bullet hell-type sequences that take place in between each of your moves. You’ll need to avoid their attacks a few times before you can actually do whatever it is you need to do to be able to “Spare” them. And every enemy’s attacks are different. That horse mermaid thing attacks you with flexing arms and beads of sweat. The dog enemies might bark at you sometimes, and other times they might just lie there and look at you, doing nothing at all. It’s clever, and it’s great.

Of course, what’s awesome here is that you can, of course, murder the shit out of everything you see, too. There’s a whole bunch of clever dialog options and actions to take if you want to play peacefully, but you also have the option to kill every enemy in your way, if you want. And the game knows.

There were several times at the beginning of Undertale when I was told about a certain way the game functions, and I said to myself, “there’s no way this can really happen through the whole game, is there?” But it did. Every single time. Undertale is consistent, sometimes ruthlessly so.

I chose to do my playthrough as a “True Pacifist”, killing no one, and it was far from easy. Every battle has a peaceful way out, but sometimes it was pretty difficult to find. But the thing is, you want to save everyone. But sometimes it’s not really that simple. I won’t explain what exactly I mean, for the sake of avoiding spoilers, but not everything is cut-and-dry in Undertale.

The story goes that a long, long time ago, humans and monsters fought a war, and the humans won, locking the monsters underground with a magical barrier that can only be opened by seven human souls. Your character, a human (and any other details about them are completely ambiguous, which is great), falls in. You begin the game by giving them a name (so you think) and setting off. You’re immediately confronted by Flowey, an evil flower (right?) who has a stupid amount of plot significance, and is basically Undertale’s Abed Nadir. He knows it’s a game. He knows you’re playing it. He’s aware of the fact that you have a save file, and isn’t afraid to mess around with it. He knows when you do a soft reset to save someone you accidentally killed, and will chastise you for it. It’s amazing.

And he’s far from the only great character. There’s two fantastic skeleton brothers, named Papyrus and Sans, who speak in the fonts their names suggest. And they’re hilarious. There are a bunch of other plot-central characters, like an anime-loving scientist recluse and a warrior fish woman, but the main characters aren’t the only ones that matter. Did you accidentally kill that little frog minion at the beginning? Don’t worry about it. Actually, yeah. You should worry about it. Because it’s gonna come back to haunt you.

Three other moments like this come to mind when thinking about how great Undertale’s plot design and choice trees really are. In the first city of the game, about a half hour in, I encountered a snowman who asked me to take a piece of him far away. I grabbed it and stuck it in my inventory, and was careful to keep it there the entire time. At the very end of the game, after all the boss battles, I got a call from a friend, who told me that I “made a snowman really happy.” I had all but forgotten about it.

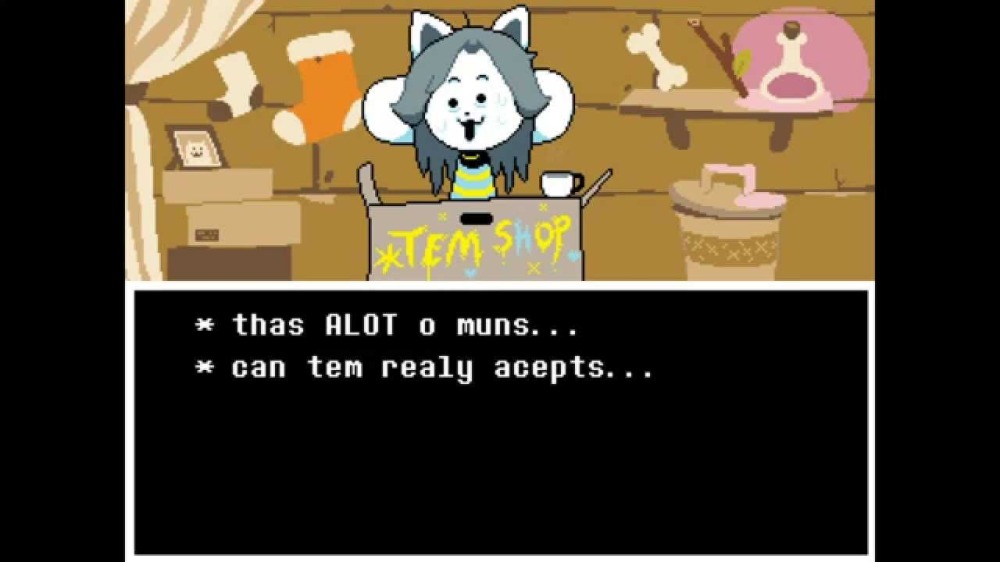

In a dark cave I stumbled upon the fabled Temmie Village, a tiny town filled with Temmies, little cat-dog things. They’re adorable. In the “Tem shop”, one of the options is “pay for college,” at a hefty 1000 gold. Naturally, I didn’t have the cash, but hours later, when I finally did, I made sure to come back and pay for Temmie to go to college. He went for about five seconds and came back with a graduation cap. He was very happy.

In the very first area of the game is a “Spider bake sale”, where you can buy food from spiders. Made of spiders. It’s weird. I had a few bucks, so I bought a spider donut. Okay. 8 hours later, I come across another spider bake sale in a lava cavern. This time they’re selling donuts for 9999G. I didn’t have it, obviously, since I’d just paid for Temmie to go to college, and didn’t feel like generating infinite money by cloning Dog Residue in my inventory and pawning it off (it makes sense in context), so I kept on going. A few rooms later, I had to fight an angry spider woman, who was mad at me for being stingy with my money, but halfway through the fight she got a telegram and let me off the hook, since I’d bought a donut from her friend at the beginning of the game.

It’s little details like that that Undertale is full of, and it goes to great lengths to make all of its characters lovable and hilarious, from Sans and Papyrus bickering about spaghetti, to the anime-loving Alphys posting on social media that she’s about to post a selfie, and then putting up a picture of a garbage can with a sparkly filter. It’s great because that’s exactly how anime fans are, and only internet denizens would know it.

Undertale has tons of these little in-jokes and references to gaming and internet culture, and doesn’t hesitate to turn your expectations on their heads. One of the boss fights can be immediately finished by running away. Want to beat the “Tsunderplane”? Get close. But not too close. Want to go on a date with a skeleton? Sure, knock yourself out. Also, the fish with the spear is going to teach you how to make spaghetti. Okay.

Undertale can feel a little plodding at times, and it seems like it’s mostly just fun and games, but I recently realized that that’s probably because I was being a nice guy. I have no doubt in my mind that things would have been drastically different if I’d killed anyone.

Which leads to one of my few complaints about Undertale. This might get a little spoiler-y, but I won’t get too detailed. I played the game on the “True Pacifist” route, and it was basically all cute, fun-and-games type stuff. Until the end. Then everything went straight to Nopeville, USA. Like I said, I won’t spoil anything for you, but holy shit. The final boss is pants-wettingly terrifying. And some of the post-game stuff to complete that route is equally spoopy. It couldn’t’ve helped that I was playing this in the darkness of my living room, alone, last night at around 12:30, but even still. [“couldn’t’ve” is probably not a word.]

I’m not saying it’s a bad thing that the game suddenly and without warning becomes scary, indeed it does so in a way that still subverts expectations (shutting your game off and corrupting save files and the like), but for someone who was playing through the game as a nice guy, it was jarring and seemed a little undeserved.

That said, the endgame is some of the best the game has to offer, and I urge you to check it out. If you sit down to play Undertale, play the whole thing. It really needs to be played in its entirety to understand its whole impact and what makes it just such a great game. Undertale is so far the only game I’ve encountered whose story can’t be told as anything else but a game, and for that it at least deserves a look.

Undertale knows it’s a game, it knows you know that it knows it’s a game, and it enjoys climbing in your brain and dicking around in there, all the while with a smile on it’s face.

After all, down here … it’s kill or be killed.